Daijiworld Media Network – Mangaluru

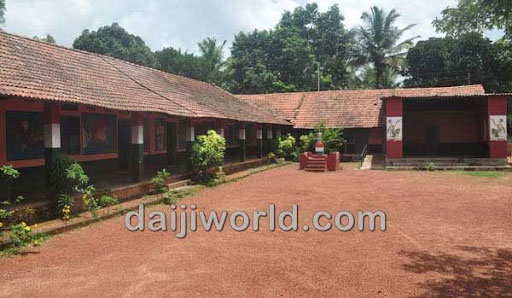

Mangaluru, Aug 25: In a deeply concerning development, 90 schools in Dakshina Kannada district have shut down over the past five years, with the Sullia and Puttur regions being the most affected.

The closures, which cut across government, aided, and unaided schools, reflect a growing crisis in the region’s primary education system — particularly in rural and semi-urban areas.

Most of the institutions closed were lower and upper primary schools, and the primary cause has been zero student enrolment, driven by factors such as declining birth rates, migration, lack of basic infrastructure, and waning parental confidence in government-run education.

According to data from the Department of Public Instruction, the closures unfolded steadily over the years.

In the academic year 2021–22, two government schools shut down alongside eight aided and ten unaided schools. The following year, 2022–23, saw the closure of four government, nine aided, and nine unaided schools.

In 2023–24, three government schools closed, along with eight aided and two unaided institutions. The trend continued into 2024–25, with two more government schools shutting down, joined by seven aided and six unaided schools.

The most dramatic surge occurred in the current academic year, 2025–26, during which eight government schools were closed — the highest so far — in addition to ten aided and two unaided institutions. This brings the total number of school closures over the five-year span to 90, comprising 19 government, 42 aided, and 29 unaided schools.

Among all regions, Sullia and Puttur have witnessed the sharpest decline, with multiple schools in these areas, including government-run institutions, closing their doors due to a total lack of students. In 2025–26 alone, three government schools in each of these two taluks ceased operations.

Yashoda Kotian, head of the education-focused NGO Daari, attributed this alarming trend to two main factors. First, she pointed to a declining interest among parents in enrolling their children in government schools, often due to perceptions of poor quality or lack of English-medium instruction. Second, she criticised the government’s failure to appoint teachers to schools with low student numbers, calling it an act of irresponsibility that accelerates the decline of enrolment and ultimately leads to closures.

In response, Dr K V Trilok Chandra, commissioner of the Department of Public Instruction, stated that government schools are now being restructured to provide a bilingual medium of instruction in both Kannada and English, aiming to boost enrolment and learning outcomes. He also noted that basic infrastructure upgrades are ongoing across the district.

Dr Chandra emphasised that schools are not closed abruptly, but only after thorough review and when enrolment continues to remain low despite intervention.

Nevertheless, concerns persist. The unprecedented closure of eight government schools in a single year — more than any previous year — has sparked debate about the future of government education in the region. While aided and unaided schools have also been affected throughout the five-year period, the rise in government school closures suggests a deepening trust deficit among local communities.

The long-term implications are serious. The closures have the potential to widen educational inequality, as families from lower-income backgrounds may struggle to access private schools, especially in remote areas. With nearby schools shutting down, many students face longer travel distances or drop out of the education system entirely.

Education activists and local stakeholders have called for immediate, multi-pronged action. Suggested measures include rebuilding public trust in government schools through transparent reforms, establishing model bilingual schools in rural zones to cater to parental demand, ensuring timely teacher recruitment, and investing in basic infrastructure and digital learning resources. Where necessary, the government could consider merging under-enrolled schools or providing transport assistance rather than opting for outright closures.

Without urgent and inclusive intervention, Dakshina Kannada — once regarded as a model district for education in Karnataka — risks a steady erosion of its public schooling system. As enrolments fall and closures mount, the future of rural education in the district hangs in the balance.